NUCLEAR FICTION NEWSLETTER, #14

- lschover

- Aug 16

- 5 min read

More Manhattan Project Novels and a New Nonfiction Book

Lately I feel pulled between setting up publicity ops for my novel that will be published in January, and trying to work on my new women’s fiction novel with my two online critique groups. I am still hoping to have a first draft finished when I go to the Kauai Writer’s Conference in November and attend a master class workshop. Despite being “retired” I feel like I am falling behind! I did want to mention several more Manhattan Project books, however, that are definitely worth a read.

I read Hill of Secrets a few months ago. The author, Galina Vromen (@GalinaVromen), is a journalist. This is her debut novel set in Los Alamos during World War II. It was published by Lake Union Press and was a Kindle First Reads choice, making me very jealous! I ordered the book eagerly when I saw it was being published. Full disclosure, Galina was kind enough to blurb Fission after we compared notes on a video call. However, my comments are my unbiased opinion.

I know how important it is to be meticulous about Manhattan Project history, as well as the difficulty of creating female characters who illustrate the lived experience of the WWII years, but will also resonate with the contemporary reader. I think this novel succeeds, providing a realistic introduction to the world of Los Alamos during the war, and extending the focus on the celebrities of the movie Oppenheimer to the diverse people who made up most of the team. Vromen uses radio and newsreel broadcasts to ground the reader in the war events that create a context for the progression of the team at Los Alamos in creating the atomic bomb (a device I also used in Fission). The novel also portrays the tensions of secrecy, with only a core group of people knowing about the purpose of the Manhattan Project.

Hill of Secrets takes a chance with some unlikely plot elements that could strain the reader’s credulity, although I think Vromen pulls them off. One is a close friendship between 16-year-old Jewish immigrant Gertie and sophisticated art restorer Christine, the wife of a project scientist, and at least ten years older. The author manages to create a relationship that forms a believable backbone for the plot. Both young women are individualists who do not conform to gender expectations of the era. The novel highlights the increasing depression of Gertie’s refugee family from Nazi Germany as the fate of the relatives they left behind becomes clear. Two other intimate relationships also involve a surprising age gap. One is the extramarital affair that develops between Christine and Gertie’s scientist father, a brilliant, but melancholy, and physically unprepossessing refugee. Since Christine is beautiful and young, with a handsome, if somewhat self-absorbed husband, her attraction to this particular man is unexpected. The other is Gertie’s dating Jimmy, a non Jewish, 23-year-old from the Special Engineers Detachment, with full approval of her father. I do not want to include any more spoilers, so I will let readers discover the fate of these characters by reading Hill of Secrets.

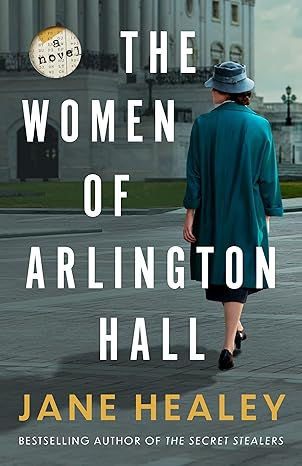

The Women of Arlington Hall by Jane Healey (@JaneHealey) was just released. Although it is set in the years just after World War II, it explores the world of cryptographers who cracked the Soviet codes in the real life Venona Project, leading to the arrests of atomic spies Klaus Fuchs, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, and their collaborators. Healey is an accomplished author of historical fiction, and tells the story through the friendships and romances of three fictional young women who work on the decoding project. Healey has a gift for using everyday life and dialogue to advance the story, without obvious historical exposition. I found myself empathizing with each of the characters, especially the heroine, Cat Killeen, a working class, Radcliffe misfit who has a stunning talent for cryptoanalysis. The paranoia of the McCarthy era pervaded the plot, and even J. Edgar Hoover made an appearance. My one reservation is the way the major characters almost gloated over the arrest of the Rosenbergs and Fuchs, although Cat does have some moral reservations over the accusations of Ethel Rosenberg. After immersing myself in the history of atomic spying during the Manhattan Project, I realized that at worst, the successful agents only advanced the Soviets’ acquisition of the bomb by several years, and that many of the scientists involved in the project wanted to create a world organization including the Soviets to regulate atomic weapons and energy. I think the execution of the Rosenbergs, particularly Ethel, was an example of government brutality. In other respects, however, I found the resolution of the novel satisfying. It is definitely an enjoyable read if you like Cold War historical fiction.

I also just finished reading the brand new nonfiction book, The Devil Reached Toward the Sky: An Oral History of the Making and Unleashing of the Atomic Bomb by well-known author Garrett Graff (@vermontgmg) (also see this interview). I personally did not learn a good deal of basic information, since I had already read so many histories of the Manhattan Project, as well as delving into many primary interviews and oral histories, but I did find many nuggets that expanded my insight. I very much admire how Graff weaves a coherent narrative out of direct quotes from major figures in the development of the atomic bomb as well as more minor witnesses to that time. It takes a great skill as well as extensive research, kind of like a very detailed, Ken Burns documentary in purely written form. Even though I knew the facts, hearing the emotions and attitudes from a first-person perspective really gave me an understanding of how people experienced that era. I think most readers will learn a vast amount.

This book also really solidifies my feeling that we attribute guilt to the people involved in the Manhattan Project based on our contemporary view of the horrors of potential nuclear war, discounting the limited knowledge at that time of how destructive weapons of mass destruction would soon become. We forget the magnitude of World War II in terms of global civilian and military casualties and the deliberate mass atrocities that were committed. American generals and government officials saw little alternative to using the atomic bomb to end the war. Graff does an excellent job of including the experiences of the Japanese civilians of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, unlike the frequent criticism of the movie Oppenheimer for glossing over that devastation. However, by using narratives predominantly from that era, Graff only touches lightly on the idea that the use of the bomb was as much about intimidating the Soviets as about forcing Japan to surrender.

Comments